The Best Ways to Naturally Reduce Methane in the Gut.

This article explores The Best Ways to Naturally Reduce Methane in the Gut, offering proven strategies to improve your digestive health and overall well-being. By incorporating natural remedies and dietary adjustments, you can effectively minimize methane levels in your Gut, leading to a more comfortable and healthy digestive process.

If you’ve ever experienced digestive discomfort, you know how crucial it is to maintain a healthy gut. One common issue many people face is excessive methane production in the digestive system, leading to bloating, gas, and other uncomfortable symptoms.

Whether you’re looking for simple lifestyle changes or specific dietary insights, this guide will provide the tools you need to naturally achieve a balanced and healthy digestive system. Discover how these methods can enhance your gut health and take a tangible step towards improved digestive comfort.

Understanding Methane and Its Effects on the Gut

Methane is produced by methanogenic archaea, a specific microorganism that thrives in the digestive tract. These archaea convert hydrogen gas and carbon dioxide into methane gas. While some methane production is normal, an overgrowth of methanogenic archaea can lead to methane-dominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), also known as intestinal methanogen overgrowth (1).

Excess methane in the Gut can slow food transit through the intestines, leading to constipation-dominant IBS, bloating, and abdominal discomfort. It can also affect the absorption of nutrients, contribute to malnutrition, and increase the risk of inflammatory bowel disease (2). Methane SIBO sufferers often experience a variety of gastrointestinal symptoms, making it crucial to identify the root causes and implement effective treatment plans.

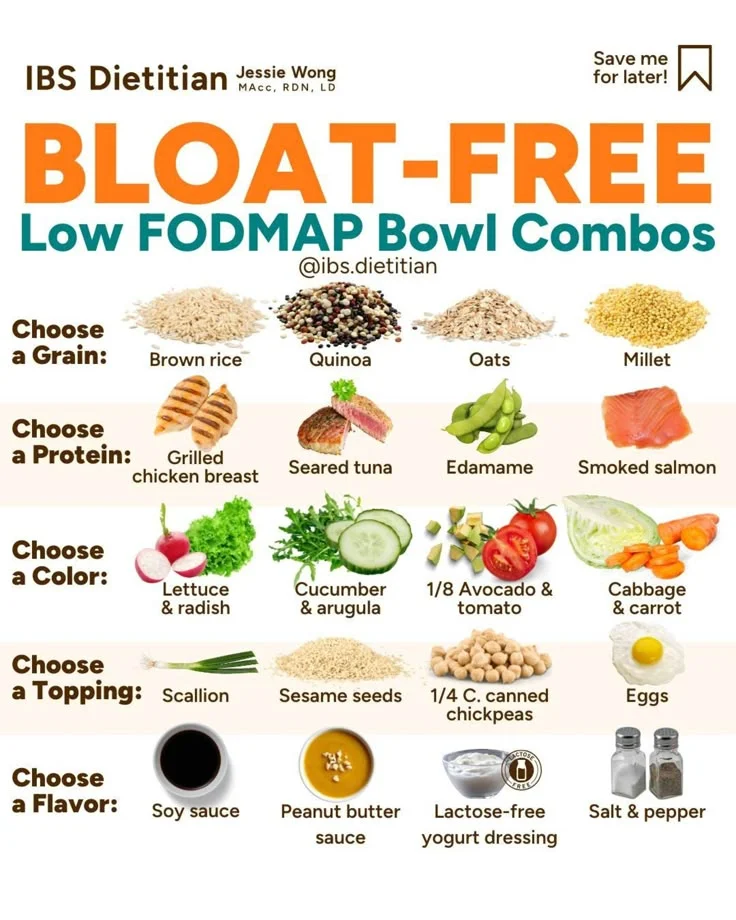

Follow a Low-FODMAP Diet

FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) are a group of carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and can be fermented by gut bacteria, leading to gas production, including methane. Following a low-FODMAP diet can help reduce methane production and alleviate symptoms of methane-dominant IBS and SIBO (3).

A low-FODMAP diet involves avoiding high-FODMAP foods such as wheat, dairy, legumes, and certain fruits and vegetables. Instead, focus on low-FODMAP alternatives like rice, quinoa, lactose-free dairy, and certain leafy greens. Working with a registered dietitian ensures you follow the diet correctly and get all the necessary nutrients (4). A specific carbohydrate diet is another option that can help manage SIBO symptoms and reduce methane levels.

Incorporate Probiotics

Probiotics are beneficial bacteria that can help restore balance in the gut microbiome and play an essential role in managing methane SIBO. Certain strains of probiotics, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, have been shown to reduce methane production and improve symptoms of methane-dominant IBS and SIBO (5).

When choosing a probiotic, look for a high-quality supplement that contains strains studied explicitly for their ability to reduce methane, such as Lactobacillus reuteri or Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis (6). Start with a low dose and gradually increase to allow your gut to adjust. Probiotics can also help combat the overgrowth of hydrogen-producing bacteria, which can contribute to methane production.

Try Herbal Antimicrobials

Herbal antimicrobials, such as berberine, oregano oil, and garlic, have been used traditionally to combat bacterial overgrowth and reduce gas production in the gut. These herbal remedies have antimicrobial properties that can help reduce methane levels and improve symptoms of SIBO (7).

Berberine, in particular, has been shown to inhibit the growth of methanogenic archaea and reduce methane production in the gut (8). You can take berberine as a supplement or consume foods rich in berberine, such as goldenseal, Oregon grape, and barberry. Other herbal treatments, such as guar gum, have also been studied for their potential to reduce methane levels and improve gut function.

Increase Fiber Intake

While it may seem counterintuitive, increasing your intake of certain fiber types can help reduce methane production in the gut. Soluble fiber, such as psyllium husk and flaxseed, can help regulate bowel movements and relieve constipation, which is often associated with methane-dominant IBS and SIBO (9).

Start by gradually increasing your soluble fiber intake to avoid gas and bloating. Aim for 25-30 grams of fiber daily, and drink plenty of water to help the fiber move through your system (10). However, be cautious with insoluble fiber, as it can exacerbate symptoms in some individuals with methane SIBO.

Manage Stress

Stress can significantly impact gut health and methane production. Chronic stress can alter the gut microbiome’s composition, increase methanogenic archaea’s growth, and worsen digestive symptoms (1). Stress management techniques like meditation, yoga, deep breathing, or time in nature can help reduce stress and improve gut function.

Regular exercise can also help reduce stress, improve gut motility, and contribute to weight loss, benefiting individuals with methane SIBO (12). Incorporating these lifestyle changes into your daily routine can help manage stress and reduce the risk of methane SIBO.

Consider Intermittent Fasting

Intermittent fasting, which involves alternating periods of eating and fasting, has been shown to improve gut health and reduce methane production. Fasting can help reset the gut microbiome, reduce the growth of methanogenic archaea, and improve methane levels in the gut (13).

There are several approaches to intermittent fasting, such as the 16/8 method (fasting for 16 hours and eating within an 8-hour window) or the 5:2 method (eating normally for 5 days and restricting calories for 2 days). Choose a method that works for your lifestyle and consult a healthcare provider before starting (14). Intermittent fasting can also help improve the absorption of nutrients and reduce the risk of small intestinal fungal overgrowth.

Stay Hydrated

Drinking plenty of water is essential for maintaining healthy digestion and reducing methane production. Water helps move food through the digestive system, prevents constipation, and contributes to the gut’s overall health (15).

Aim for at least 8 cups (64 ounces) of water daily, and increase your intake if you are active or live in a hot climate. Herbal teas and broth can also increase your daily fluid intake (16). Staying hydrated can help improve gut function and reduce the risk of methane SIBO.

"Hydration is essential for health; it helps in nutrient absorption, temperature regulation, and waste elimination." —

Dr. David Ludwig Tweet

Consider an Elemental Diet

An elemental diet, which involves consuming a liquid diet of easily digestible nutrients, can help reduce methane production and improve symptoms of SIBO. This diet gives the body the necessary nutrients while giving the digestive system a break from processing solid foods (17).

An elemental diet can help reduce the growth of methane-producing bacteria and improve overall gut health. It is crucial to work closely with a healthcare provider to determine if an elemental diet is appropriate for your specific situation and to monitor your progress, ensuring you feel supported and guided in your journey to better digestive health.

Address Low Stomach Acid

Low stomach acid can contribute to the overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestine, including methane-producing bacteria. Addressing low stomach acid through digestive enzymes and other supplements can help improve digestion and reduce the risk of methane SIBO (19).

Working with healthcare providers to determine if low stomach acid contributes to your symptoms is important and to develop a treatment plan that addresses this underlying cause (20).

Consider a SIBO Breath Test

A SIBO test, such as a lactulose breath test, can help identify methane-producing bacteria in the small intestine. This test measures the hydrogen and methane gas levels in the breath after consuming a specific sugar solution (21).

If the test results indicate the presence of methane SIBO, a healthcare provider can develop a treatment plan that addresses the specific bacteria causing the overgrowth. This may include dietary changes, herbal supplements, and other interventions (2).

Address Underlying Conditions

Methane SIBO can be associated with other underlying conditions, such as celiac disease and lactose intolerance. Addressing these conditions through dietary changes and other interventions can help improve gut health and reduce the risk of methane SIBO (23).

It is important to work with a healthcare provider to identify any underlying conditions contributing to your symptoms and develop a holistic approach to treatment (24).

Conclusion

Dietary changes, supplementation, and lifestyle modifications can naturally reduce methane in the gut. Following a low-FODMAP diet, incorporating probiotics and herbal antimicrobials, increasing fiber intake, managing stress, considering intermittent fasting, staying hydrated, and addressing underlying causes can help reduce methane production and improve digestive health.

Remember that everyone’s gut is unique, so finding the right combination of strategies that work for you may take trial and error. If you continue to experience symptoms despite making these changes, consult a healthcare provider to rule out other underlying conditions and develop a personalized treatment plan.

The latest research and clinical trials continue to explore the best ways to manage methane SIBO and other gastrointestinal conditions. A systematic review of the available evidence can help guide clinical practice and improve outcomes for individuals with methane SIBO.

The good news is that with the right approach, it is possible to significantly reduce methane levels and improve overall gut health. By working with a healthcare provider and implementing a comprehensive treatment plan, you can take control of your digestive health and enjoy a better quality of life.

Sources:

Sahakian, A. B., et al. (2010). Intestinal methane production is associated with constipation. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 5(3), 64-649. Pimentel, M., et al. (206). Methane, a gas produced by enteric bacteria, slows intestinal transit and augments small intestinal contractile activity. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 290(6), G1089-G1095. Staudacher, H. M., et al. (201). Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 24(5), 487-495. Halmos, E. P., et al. (2014). A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology, 146(1), 67-75. Ringel-Kulka, T., et al. (201). Probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07 versus placebo for the symptoms of bloating in patients with functional bowel disorders: a double-blind study. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 45(6), 518-525. Kim, H. J., et al. (205). A randomized controlled trial of a probiotic combination, VSL# 3, and placebo in irritable bowel syndrome with bloating. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 17(5), 687-696. Chedid, V., et al. (2014). Herbal therapy is equivalent to rifaximin for treating small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 3(3), 16-24. Zhang, X., et al. (2015). Berberine inhibits the production of methane and hydrogen in vitro. Anaerobe, 34, 151-156. Bijkerk, C. J., et al. (209). Soluble or insoluble fiber in irritable bowel syndrome in primary care? Randomized placebo-controlled trial. BMJ, 39, b3154. Eswaran, S., et al. (2013). Fiber and functional gastrointestinal disorders. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 108(5), 718-727. Konturek, P. C., et al. (201). Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach, and treatment options. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 62(6), 591-59. Johannesson, E., et al. (201). Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 106(5), 915-92. Cignarella, F., et al. (2018). Intermittent fasting confers protection in CNS autoimmunity by altering the gut microbiota. Cell Metabolism, 27(6), 12-1235. Patterson, R. E., et al. (2015). Metabolic effects of intermittent fasting. Annual Review of Nutrition, 35, 371-390. Arnaud, M. J. (203). Mild dehydration: a risk factor of constipation? European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57(Suppl 2), S8-S95. Popkin, B. M., et al. (2010). Water, hydration, and health. Nutrition Reviews, 68(8), 439-458. Pimentel, M., et al. (2012). The effect of a nonabsorbed antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 157(9), 589-596. Bures, J., et al. (2010). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 16(24), 2978-290. Saltzman, J. R., et al. (2017). The impact of hypochlorhydria on the development of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology, 8(8), e12. Yakoob, J., et al. (2018). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and its relationship with chronic diarrhea and other gastrointestinal disorders. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 34(2), 404-409. Ghoshal, U. C., et al. (2016). The diagnostic value of the lactulose hydrogen breath test in subjects with unexplained chronic diarrhea. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology, 35(3), 205-21. Rezaie, A., et al. (2017). Hydrogen and methane-based breath testing in gastrointestinal disorders: the North American consensus. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 12(5), 75-784. Tursi, A., et al. (2013). Treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowth in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 17(16), 2153-2160. Quigley, E. M. M., et al. (2018). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: roles of antibiotics, prebiotics, and probiotics. Gastroenterology, 154(2), 393-403.

The Best Ways to Naturally Reduce Methane in the Gut

Contents hide 1 The Best Ways to Naturally Reduce Methane in the Gut. 2 Understanding Methane and Its Effects on the Gut 3 Follow a

The link between Leaky Gut Syndrome and Weight Gain

Facebook Threads The content on this blog is intended solely for informational purposes. It should not be construed as professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment,

The Connection Between Gut Health and Brain Fog

The Connection Between Gut Health and Brain Fog https://cortexcannibal.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Untitled-design-1.mp4 “To keep the body in good health is a duty. Otherwise, we shall not be able

Exploring CBG for Gut Health Uses and Benefits

Facebook Pinterest The content on this blog is intended solely for informational purposes. It should not be construed as professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment,

The Connection Between Allergies and Heart Rate.

Your Heart and Allergies: Understanding the Connection and Managing Your Health” The content provided on this website is intended for informational purposes only and should

Natural Herbs for Great Dental and Oral Health Care.

Natural herbs for great dental and oral health care. Every tooth in a man’s head is more valuable than a diamond. — Miguel

Home » Cortex Chronicles and Savory Synapses » The Best Ways to Naturally Reduce Methane in the Gut